Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

If there's a phrase that can spread fear into the bones of homeowners, it's someone saying 'it looks like you have rising damp.' Enough to make a wallet twitch and your heart race, it's been the subject of home horror stories on more than one occasion.

But, what if your rising damp isn't really rising damp? The signs of damp on your walls doesn't mean it's always as bad as you fear, and how you treat the problem will be essential in preventing issues in the future.

Build expert, Ian Rock is here to explain how to know when your damp is genuinely rising damp, and when it's a case of mistaken identity.

What is rising damp?

It's hardly surprising that in a rainy country like Britain the subject of water ingress has such a firm grip on the national psyche, even spawning whole industries dedicated to battling disconcerting damp patches.

Rising damp, one of the different types of damp that can occur in the home, is, as the name suggests, penetrating damp which rises upwards from ground level into the walls of your home.

It is generally caused by a number of different problems with the damp proof course (DPC) in your home, or indeed by the lack of a DPC. It's also often harder to spot, unlike damp in roofs or lofts, which can become visible more quickly as a result of roof leaks in lofts or ceilings.

However, the concern around the topic of rising damp is understandable, as unless it's carefully managed, water has significant potential to damage and disrupt. As well as instigating decay in timber structures, over time water can erode solid masonry because it expands around 8% in volume when it freezes, exerting a pressure equivalent to two tonnes per square centimetre.

Bring your dream home to life with expert advice, how to guides and design inspiration. Sign up for our newsletter and get two free tickets to a Homebuilding & Renovating Show near you.

The good news is, these sorts of headline grabbing risks are extreme examples, and normally only arise in cases of long-term neglect.

Why is rising damp misdiagnosed?

Damp in lower walls is a subject with a significant history. It began back in the Victorian era (from 1875 to be precise) when builders started installing DPCs in the lower courses of the main walls as a barrier to deter water from the ground rising up the brickwork.

DPCs were designed to work in tandem with air brick vents set in the lower walls to encourage a healthy flow of air that naturally dries out any moisture in the walls and sub-floor.

But, when there are problems with the DPC, it means the barrier that was in place to prevent moisture ingress in your home is broken or bridged. As a result, it's often assumed, often too quickly, that blown plasterwork or dampness in the lower walls means only one thing – rising damp.

The way moisture affects old buildings has only recently started to be fully appreciated, and the automatic reaction of many mortgage lenders to the slightest sniff of damp has long been to insist on ‘essential repairs’ often resulting in sales-driven timber and damp contractors unnecessarily injecting chemical DPCs into the affected areas.

In truth, the occasional spot of damp isn’t necessarily a problem and it not unusual to need to treat damp in older properties. To a trained eye, a damp patch may reveal itself to be a relatively harmless symptom of a minor fault that can be rectified during routine maintenance.

Tthe most common cause of damp in lower walls, is in fact high ground. External ground levels should be a good 200mm or more below floor level. Common offenders include flower beds banked up against outside walls that effectively force moisture into the brickwork.

Other culprits include patios laid far too high causing bridging of DPCs, and rain splashing on hard surfaces that saturates the lower walls.

The fact is, the main walls in our homes aren’t impregnable. Water often finds its way through weak points, such as gaps that have developed where window and door frames are set into walls, and beneath defective window sills.

Cracks or eroded mortar joints can also be an invitation for rainwater to join the party. Dampness of this type is all quite logically referred to as ‘penetrating damp’.

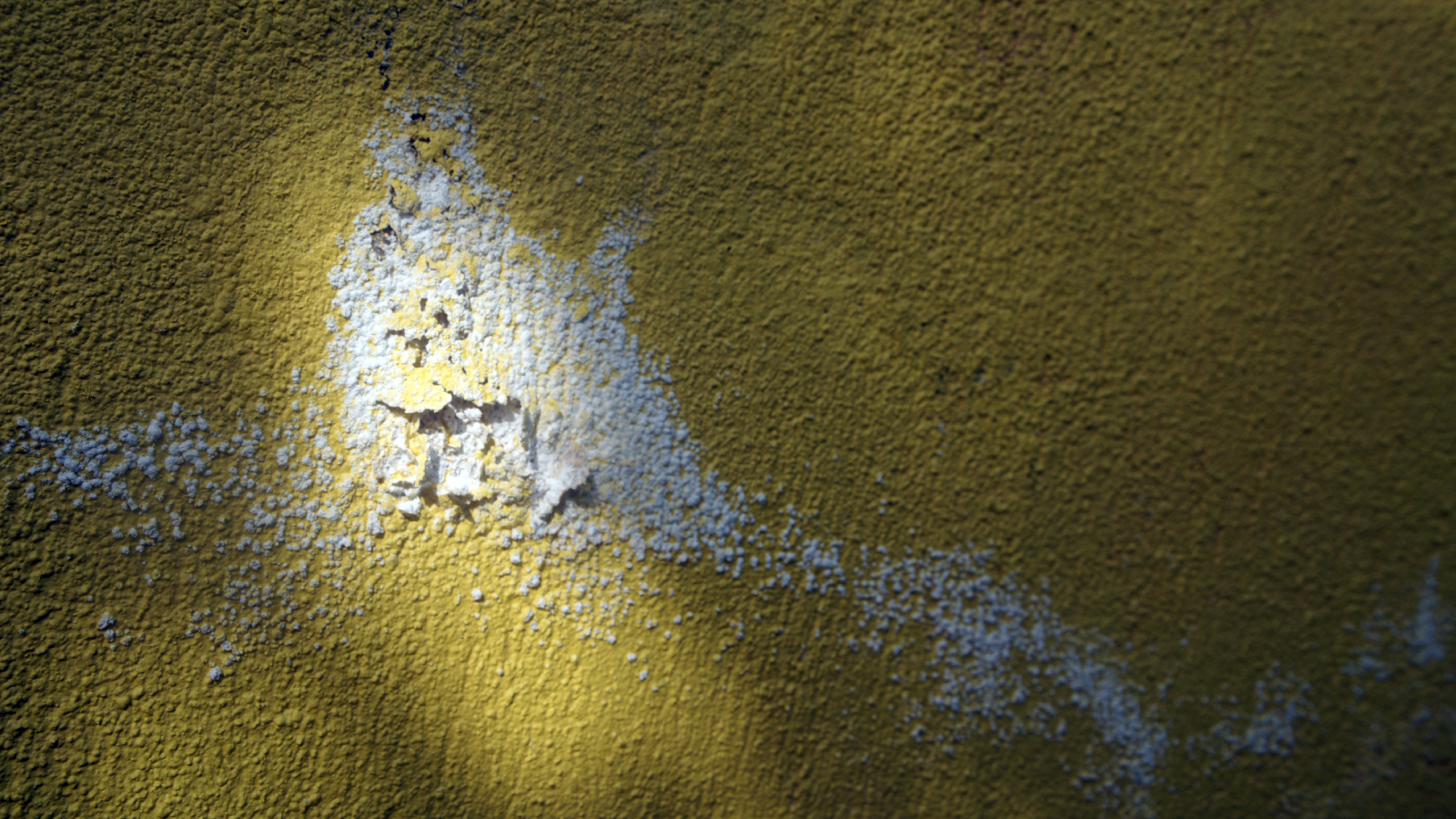

The age of a property can be a useful guide to where it is most vulnerable to moisture ingress. Many older houses with solid walls have relatively porous brickwork that can absorb a certain amount of rain. This isn’t usually a problem if the moisture is free to evaporate out again in dry weather (a process known as ‘breathing’). But where walls have been re-pointed or rendered with incompatible modern cement-based materials that are comparatively hard and brittle they have a tendency to develop fine cracks that allow rain to enter and become trapped. Modern non-breathable ‘plastic’ paints can also block damp from escaping, acting like a giant plastic bag smothering the walls.

Once trapped, damp that freezes can blow off chunks of render or erode solid brick or stonework, so the best advice is to replace any cement mortar pointing or render on older solid walls with traditional, breathable lime-based materials.

The main concern in cases where rising damp is suspected, or indeed confirmed, is whether there’s any risk of long term exposure causing rot to structural components such as suspended timber floors.

How you treat rising damp depends on the cause of the problem

The surveying profession now generally acknowledges that past advice on treating damp by injecting chemical DPCs often did more harm than good. Instead, an effective solution usually involves carrying out maintenance work carefully targeted to address the specific cause of the problem.

One of the most important factors here is the extent to which water is allowed to accumulate near the base of the walls. Where you’ve got wet, stained brick or stonework with puddles on the ground the first consideration should be cutting off the supply of water. Check for things like blocked or overflowing gutters, leaking downpipes, faulty drains or gulleys, and waste pipes that need to be fixed.

As well as lowering the ground, installing a shallow gravel-filled trench, or French Drain around the base of the walls should allow moisture to evaporate more easily.

Modern cavity walls can also harbour damp due to poor quality construction with mortar droppings or debris accumulating in the lower cavities which may need to be cleared by specialist contractors laboriously removing individual bricks.

Any badly eroded mortar joints should be raked out and repointed. It’s also worth clearing any climbing vegetation on period properties, as this can harbour damp and prevent walls from drying out. Internally, evidence of past damp problems can often be detected in plasterwork, which can retain a residue of salts deposited by water. These white salts should be brushed or vacuumed off as they can absorb moisture from the atmosphere of the room, or in severe cases re-plastering may be required.

If all else fails and an injected DPC is recommended, the most effective option is a diffusion system using Silane cream which is odourless, non-flammable and diffuses via the mortar joints without scarring the walls, so can even be applied to party walls.

In conclusion, a well-maintained building shouldn’t need special treatments to manage damp. Most problems can be remedied with common-sense maintenance.

Your first task should always be to identify the true cause. Then, once this has been resolved, keep the house heated and allow sufficient time for the walls to dry out.

For internal damp problems, try using the best dehumidifiers to prevent condensation and damp building up on your walls and windows, and if you have fixed a damp problem, follow the advice for painting over damp to get your home looking fresh and restored once more.

Chartered surveyor Ian Rock MRICS is a director is Rightsurvey.co.uk and the author of eight popular Haynes House Manuals, including the Home Extension Manual, the Self Build Manual and Period Property Manual.

Ian is also the founder of Zennor Consultants. In addition to providing house surveys, Zennor Consultants provide professional guidance on property refurbishment and maintenance as well as advising on the design and construction of home extensions and loft conversions, including planning and Building Regulations compliance.

Ian has recently added a 100m2 extension to his home; he designed and project managed the build and completed much of the interior fit-out on a DIY basis.